Twenty years ago there were 14,000 FDIC-insured financial institutions. Today that number is cut in half. The reasons are many. And yes, some are beyond our control such as population mobility, technology, and the need for some scale to invest enough to remain relevant. But, as my one-time Division Officer, Lieutenant Proper, once told me: "Be careful pointing your finger, because the other three are pointing at you."

I recently made a presentation to staffers and advisers to the Pacific Coast Banking School (PCBS) regarding what I would change in the curriculum. My theme was that if we keep teaching bankers the same things, and expect different results (i.e. not cutting our industry by half), then we are insane. I don't think I'll be invited back.

Banking is an industry that is particularly susceptible to external forces such as interest rates, business and consumer confidence, and the economy (both local and national). So if things go wrong, there is plausible deniability as to what or who is responsible. Strange that when things go right, it's difficult to find plausible deniers. But I digress.

Because of the external forces that impact results, it is typical to gravitate to holding ourselves accountable to things under our direct control... i.e. our expense budget. Volumes and balances... not my fault, there's no loan demand. Margins... not my fault, the irrational competitor down the street is being too aggressive. Profits in fee based businesses... not my fault, soft insurance market.

I find this when analyzing client profitability reports. Nobody wants to absorb the costs of support centers, such as HR, IT, and Marketing, or overhead centers such as Finance or Executive. Hold them accountable for their direct profits, because that is what they can control. It reminds me of Louisiana Senator Russell Long's quip in the 1950's... "don't tax you, don't tax me, tax that fella behind the tree." I suppose if nobody finds value in support centers to the point they agree to pay for it, we should eliminate those costs.

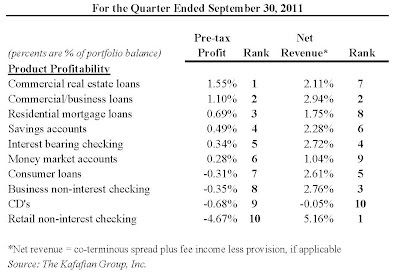

I think the answer to move our industry forward by establishing an accountability culture is to identify a few, transparent metrics that are consistent with strategy that hold managers accountable for continuous improvement. To overcome macro-economic factors, use trends and comparatives. For example, if you hold branch managers accountable to continuously improve their deposit spreads, compare them to the average and top quartile deposit spreads of all of your branches. The result of this accountability should be continuous improvement in your bank's cost of funds compared to peers. But instead of managing at the "top of the house" (i.e. bank's total cost of funds), we burrow down to the managers responsible for generating funding.

But since there is some art and science that goes into developing management information to establish accountability at the ground level, those managers that don't shine will frequently lob darts onto the results. But bankers that are committed to identifying and executing on a strategy that differentiates them from the remaining 7,000 FIs, should identify the metrics that correlate to successful strategy execution.

And when managers challenge the message to dilute their accountability, senior leaders must be exactly that...

Leaders.

~ Jeff